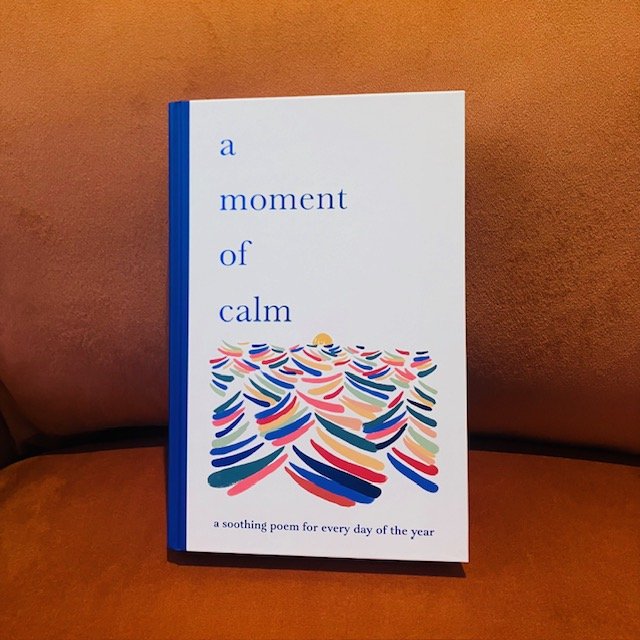

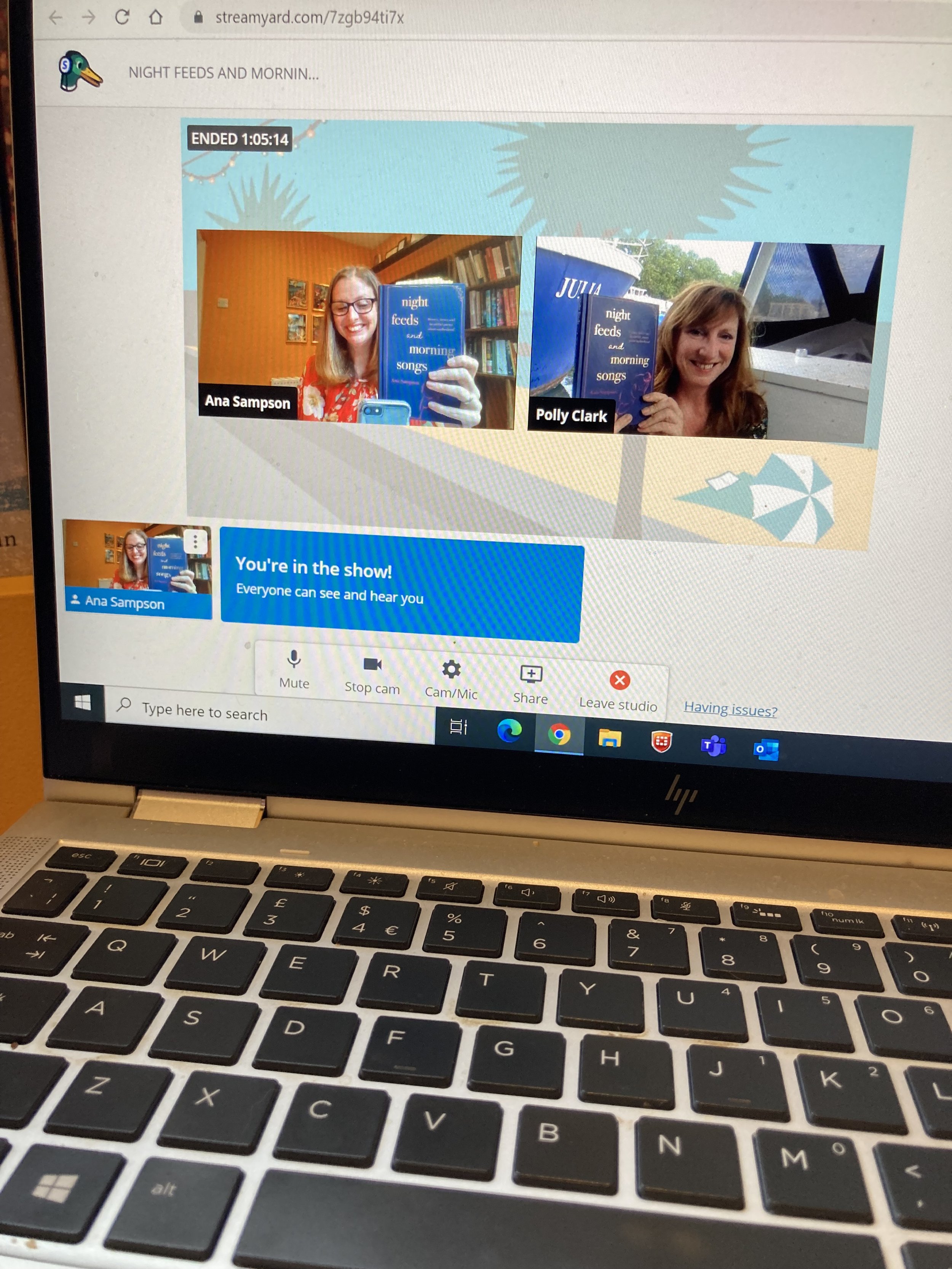

A Moment of Calm: Poetry to Soothe and Heal

We scamper through a modern world in which we are all, it seems, expected to fill Kipling’s unforgiving minute with much more than sixty seconds’ worth of distance run. It’s hard – even in those last minutes of the day – to step off the ever-spooling treadmill and indulge ourselves with a few moments of real calm, even though we long to do so. A Moment of Calm is the longest anthology I have ever edited, with a soothing poem for every day of the year included. I hope this book, and the verses within it, will prove your passport to a little space of serenity whenever a reader lifts it from the shelf. This is the book’s introduction.

“Then close thine eyes in peace, and sleep secure,

No sleep so sweet as thine, no rest so sure.”

- On a Quiet Conscience by Charles I (1600 – 1649)

It has been a delightful task to gather these gorgeous poems. Many of them are explicitly about evening and night, and shoot us into the sleeping skies. Up among the stars, in dark and dizzying vastness, today’s petty struggles seem to melt away. We have always felt this, it seems. Moons and planets turn gracefully; stars give out their steadfast gleam. We find space – pun intended – in our minds to contemplate, and to rest. When the distances we travel in imagination are so great, nobody is still running.

Though my soul may set in darkness, it will rise in perfect light;

I have loved the stars too fondly to be fearful of the night.

- The Old Astronomer to his Pupil by Sarah Williams (1837 – 1868)

Many of these night sky rhymes are well known to us from childhood, conjuring up memories of sleepily half-remembered friends – owls, pussycats, old ladies with brooms, sailors in the night sky – with soothingly familiar music. Might we not, as we once did, wish upon a star or tell ourselves a bedtime story? Do we not need wishes and stories, now, more than ever?

“All night across the dark we steer;

But when the day returns at last,

Safe in my room, beside the pier,

I find my vessel fast.”

- My Bed is a Boat by Robert Louis Stevenson (1850 – 1894)

Some of these writers offer recipes for a peaceful life. It has little to do with striving and bustle, and nothing at all with status and success. It has everything to do with tranquillity, simplicity and contentment.

“My mind to me a kingdom is” - Sir Edward Dyer (1543 – 1607)

I love the thought of these poets composing this sage advice centuries ago. Picture the desk at which they sat, the pen they wielded, the candlelight and the deep, pre-industrial silence around them. With what astonishment might Sir Edward Dyer (1543 – 1607), John Dryden (1631 – 1700), Susan Coolidge (1835 – 1905) or even Charles I have glimpsed us, pausing our frenetic lives for just a moment, in alien rooms, poring over these pages? How would they feel to know that we are still, even now, taking in their beautiful, wise words to calm our hearts and set our course straight?

“Take heart with the day and begin again” - New Every Morning by Susan Coolidge (1835 – 1905)

There are hymns here to warm rooms on winter nights, when we light the lamps and hunker down. I hope they kindle warmth for you. These are words composed to bring us ease and coziness, the literary equivalent of a blanket to wrap ourselves in.

“The house-dog on his paws outspread

Laid to the fire his drowsy head”

– from Snowbound: A Winter Idyll by John Greenleaf Whittier (1807 -1892)

If we cannot hibernate – however appealing it sometimes seems – we can, through poetry, grant ourselves a few holy minutes each day. We connect in these quiet moments with the poet who set down these thoughts for us, however distant their world and their time might be to ours. Their poems act as a springboard into a reverie that is uniquely our own, and it is a rare and precious gift to hear our own still, small voices, so often buried in the clamour of the raucous everyday.

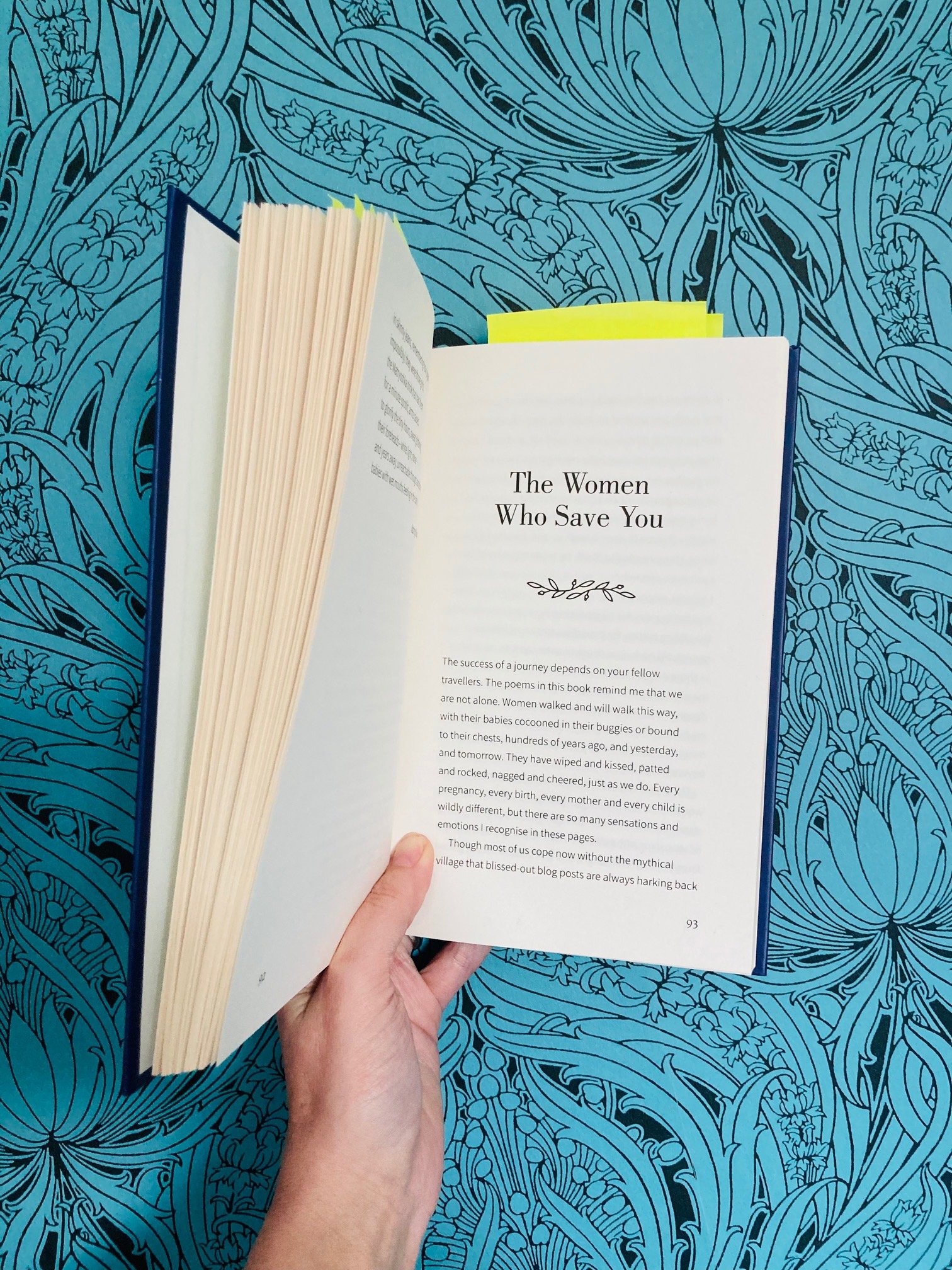

As the year turns, and the earth slowly awakens, we leave poems about the held breath of a snowy landscape, and look to those celebrating the green beauty of spring, and the easy pleasure it brings. The countryside and coastline have long soothed, inspired and nourished, but for the days when a restorative ramble in the fresh air is off the cards, this book is designed as an ejector seat. Here are songs of balmy evenings and gently rushing waves, and anthems to the perfect blue of a dimming spring sky or a sultry summer night. We might sink beneath the waves to drift with mermaids or drowsy seal pups, we might set sail on the waters of an unruffled loch… A poem and our own imaginations can take us anywhere, in mere moments, without the need for packing or palaver.

“There is a peace in the depths of the sea,

Like the peace that is deep in the heart of me.”

– Deep Peace by Josephine Royle

Each of these poems is an escape hatch, and through it we are able to tumble out of the day’s shopping lists and inboxes into a quiet and comfortable place. There are words here of love and leisure, of stars and softness, of coziness and contentment, of all the many thoughts we can gather about us to feel warm and safe. Life moves pretty fast, and so do we. I hope that in these pages, through these words – whether written many centuries ago or in recent years – you are given the gift of stillness, and are soothed.

“Right good is rest.” - For the Bed at Kelmscott by William Morris (1834 – 1896)

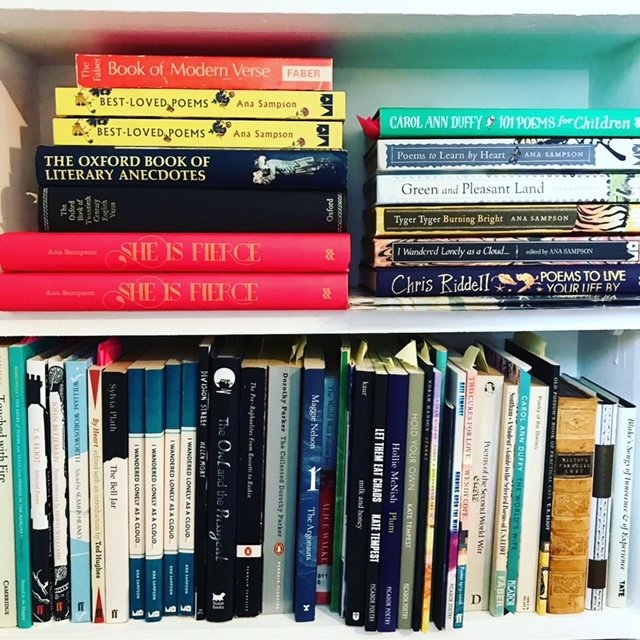

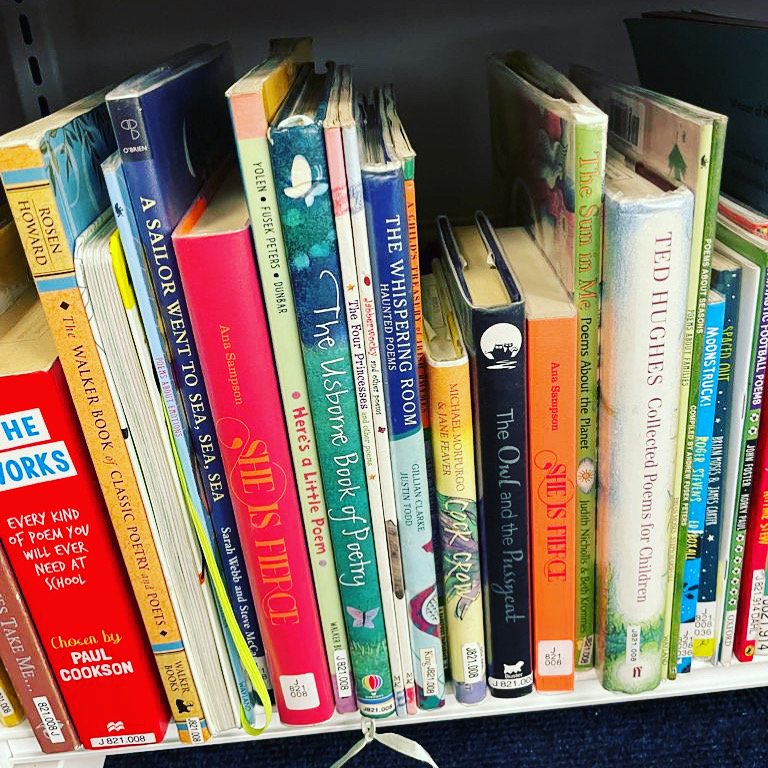

A Moment of Calm: A Soothing Poem for Every Day of the Year, edited by Ana Sampson is out now, published by Laurence King.