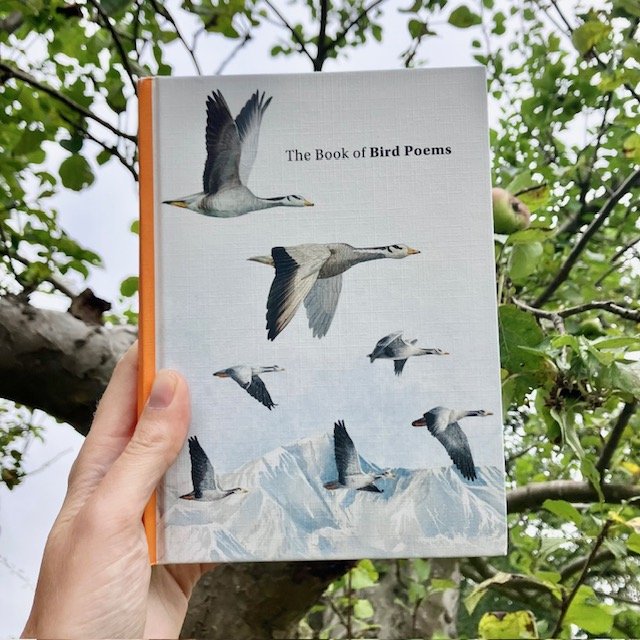

Giving You Wings: The Book of Bird Poems

Imagine a day without birds.

It’s a terrible thing to picture, wherever in the world you are and whatever birds can be seen from your window. The held-breath silence of an empty wood or the desolation of a bare coastline is not to be contemplated. Part of the reason that wild birds hold a special place in our hearts is because we live alongside them almost everywhere on earth.

Birds are busy, always. Superficially we know much about their habits and drives, but to watch them in action is always to glance into a mysterious world, one that’s bursting with activity. They are striving and feeding, hunting and wooing, bathing and conspiring, these little daughters of dinosaurs. Round and cheerful like the robin or graceful and balletic like the flamingo, infinitely varied and forever engaged in their urgent secret pursuits, it is no wonder that we are so fascinated by them. And perhaps there is a special relationship between the avian world and writers: who else, after all, will have spent so many hours gazing out of their windows?

Last year, my daughter and I rose early and ventured out into the nearby wood as dawn broke across the winter sky. (I’m not hardy enough to do this in summer, which would require a 4.30am alarm, but I could brave a January sunrise.) As the horizon lightened, little by little, the trees around us came alive. As well as the tick of a woodpecker, we heard the tumbling carols of the blackbirds, the insistent cheep of sparrows, the yodel of finches and the impudent sawing of the crows echoing around us.

How can we describe, in mere words, the sound of birdsong?

This is the task so many of the poets in The Book of Bird Poems, set themselves, and I believe they come as close as fragile language can to that holy sound. We can see how closely they have watched their subjects to paint these portraits. Blake observes a lark whose ‘little throat labours with inspiration, every feather / On throat and breast and wings vibrates’, and Hardy’s Darkling Thrush is aged, ‘frail, gaunt, and small, / In blast-beruffled plume’, making his ecstatic hymn more moving still. Flora Cruft’s Night Birds have ‘lungs the size / of spider heads’ from which they herald the dusk.

When birds sing, no matter how many times we have heard the sound before, it is astonishing. It can lift our spirits when we languish in the heart of darkness. I have included Adelstrop here – the beautiful, deservedly famous poem by Edward Thomas. Thomas never returned from the Western Front, but he left us his deathless words and the song of a long gone blackbird, with the choirs of Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire rising behind it. It is an exquisite legacy.

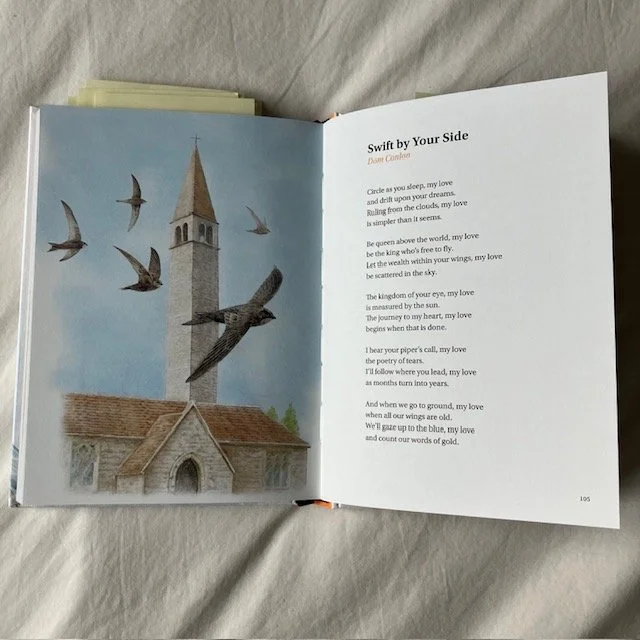

Just as the dawn and dusk choirs punctuate our progress through the day, birds bind us to the changing seasons. The exhilarating babel of spring, when some return from wintering away and most look to nest and breed, can lift the most jaded of souls. The world comes alive, then, with their song and bustle, from the busy sparrows to Longfellow’s returning stork. For many poets in the British Isles, tracing back centuries, the calls of the cuckoo and buzzing twitter of swallows ring in the summer.

As shadows lengthen and trees turn, the sight of migrating birds on the wing – like Yeats’ swans at Coole – is a timeless reminder of the seasons’ steady roll. The birds answer some deep and ancient pull, and an answering note is struck in us below, as we gather in our summer selves and turn our minds to wintering. Through the cold, dark months, those that stay continue to serenade us, though, and their song never fails to lift our hearts. For a moment when we lift our heads and hear them we, too, dip and soar and ride the wind. I hope these poems give you wings.

Extracted from The Book of Bird Poems, edited by Ana Sampson and illustrated by Ryuto Miyake.